Mar 22 2014 (a 24 minutes read)

It’s pitch black. You’re likely to be eaten by a grue

Lessons from video games

This is the full text of my World IA Day 2014 closing keynote in Bristol discussing formal elements, dramatic elements, and spatial elements in video games and what lessons are there for new media design. The complete slide deck with speaker notes can be found on SlideShare

(Lights off in the room. The screen is completely black. A white caption reads“Only confirmed photo of a grue in the wild)

What is a grue? Well, we do not really know. But grues were invented as a substitute for the bottomless pits that used to litter even the attics of text-based exploration games such as Zork. Which made for very impractical set ups. Grues were a means to control game dynamics and game space: if it was pitch black, they were going to get you, and you had to either leave in a hurry or light a torch.

So let me light a torch to get the grues running, and we will try to explain what we can learn from how and why video games create and manipulate game space.

(Lights on in the room)

Let us start with the core question. What is a game?

I will be using the framework laid out by Tracy Fullerton in her “Games Design Workshop”, as it focuses on the elements of structure, story and interaction, which are key points for any conversation that addresses user experience. Fullterton points out there are different artifacts related to the idea of “play” and “game” that differ in how they handle key elements. The most basic one is a story. A story provides no interaction. Then we have toys. Toys turn storytelling into an interactive experience but they still provide no goals. Puzzles provide a goal, so we have a slightly more structured experience with a desired future state, but we still lack one necessary element: unbalance. Games generate an outcome: someone wins and someone else loses. No winner, no game.

So Fullerton gives us a straightforward way to assess if something is a game or not. The next step is to understand what a game is made of. To illustrate this, I will use the “Prince of Persia” video game. Not the original one written and coded by Jordan Mechner for Broderbund in 1989, but the more recent UBISOFT 2003 reboot for the Sony PlayStation platform. Mechner was involved anyway, and honestly it shows.

In many ways, the 2003 “Prince of Persia” was as much a groundbreaking game as the original one was in 1989, even though other offerings had better graphics, or better controls, or better interactions at the time. Much of its charm came from how elegantly its different building blocks were integrated into the experience of playing the game. Then what are these building blocks?

In her “Game Design Workshop”, Fullerton introduces two larger categories or sets of such blocks: formal elements and dramatic elements. I add to Fullerton’s, and will explain why, spatial elements.

Formal elements are the practical building blocks, those we primarily associate with gameplay. They include the rules and procedures you necessarily have to follow to play the game, the number of players and their relationships, and any resources the game provides players. If you have roamed a level in SuperMario looking for more coins or frantically run across some nightmare 3D landscape for a “medikit”, you know what a resource is. Resources are scarce: evil designers make sure it is so. Another important formal element is outcomes. Outcomes are concerned with the “winning conditions”: how does a player get to win the game? How does another one lose? Outcomes are intrinsically connected to a fundamental characteristic of games, that they thrive on conflict. Someone has to win. Someone has to lose. The interplay of the various formal elements greatly impacts how the game creates conflict and manages unbalance.

Fullerton also considers boundaries a formal element: this is where I depart from her model. I consider boundaries, or what stands for boundaries, to be one element in a third set, the spatial set, that centers specifically on game space and the role played by spatiality and spatial primitives in the game experience.

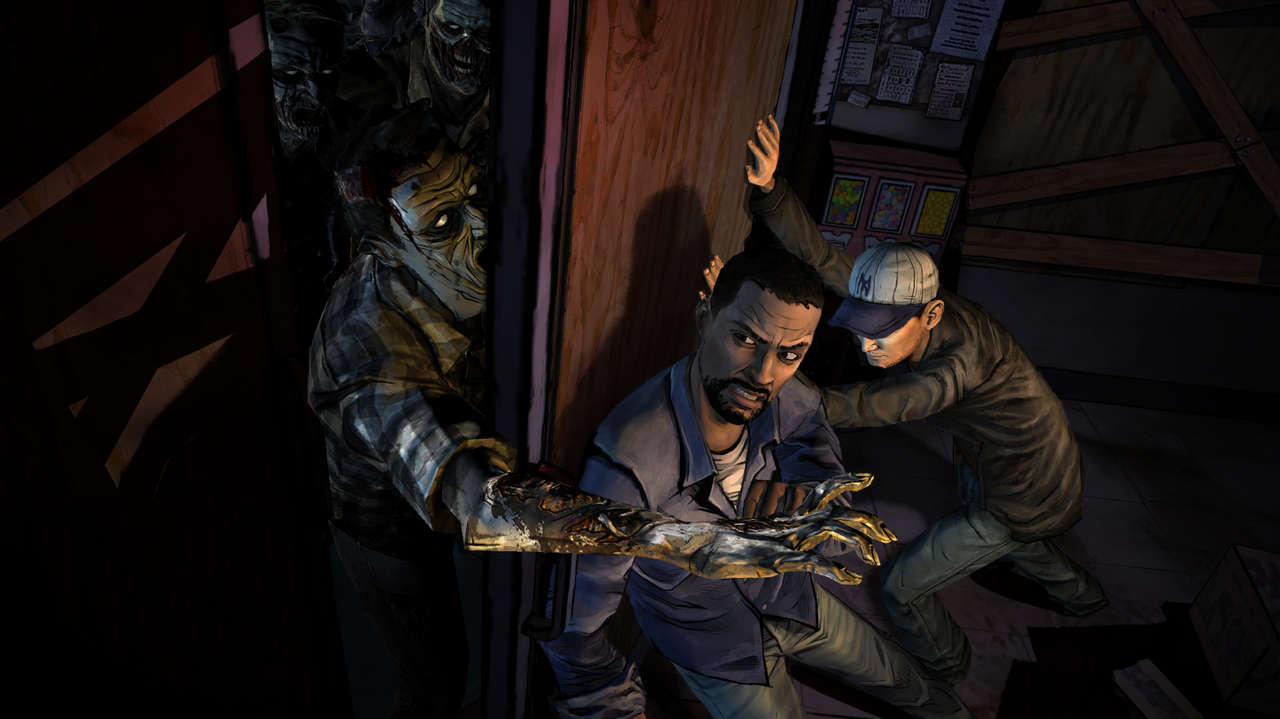

Fig. 1. Pushing a door in “The Walking Dead” video game

Fullerton then introduces dramatic elements. In the case of “Prince of Persia”, that means a narrative involving a prince (unsurprisingly) trying to repair the damage done by the imprudently release of the “sands of time” from a magical hourglass. The player takes control of the prince as he parkours and fights his way through a rather implausible palace in which everyone has been turned into a sand monster, trying to reach the Tower of Dawn where the sands can finally be sealed back inside the hourglass.

Here we can notice a first interesting shift between 1989 and 2003: in the original game, the sands of time were simply an in-game stand-in for a formal element, time, a resource, since you had 60 minutes to beat the game. In 2003, they received a whole different treatment: they became a fundamental part of the story, one of the primary dramatic elements, those that provide context and settings to emotionally tie players to the in-game mechanics provided by formal elements.

The role of dramatic elements cannot be underestimated. What sets the scene from “The Walking Dead” game in Figure 1 apart from similar games is not any formal element, but rather the way it manipulates us by means of our emotional engagement. In formal terms, players are requested to continuously press a controller button. This is not specifically fun or exciting.

If the player is successful, pressing the button will push a door close, and keep it closed, inside game space. Many other games include using a controller to push a door close, but here we have zombies on the other side of that door. Dramatic or narrative elements are very often what makes you want to go back (or not) to a game.

Dramatic elements include a premise, a way to set up a narrative thread and a coherent environment; characters, be these pawns representing roles on a numbered board, kings and queens, or just really plump birds. Through premise and characters, every single game weaves a story that is then “set” in a specific spatio-temporal context. These settings can be compared to the mise-en-scene for a movie.

Do not let distance or unfamiliarity fool you: dramatic elements are always present, but sometimes games have become so abstract or commonplace that we do not really see the premise, the characters, or the settings anymore. Monopoly is really a game about real estate and capitalism in 1920s America. Chess is about warring armies. Mancala games are about sowing and extending one’s agricultural footprint.

Dramatic elements contextualize and structure formal elements within the game, make them different, and more or less successful at engaging players. Grues, for example, are a great way to make sure players enter specific areas of a game only if some formal elements have been triggered or obtained. In this case, light, a resource. Did I mention torches are probably scarce in any game that has grues or grue-equivalents?

At this point, we could have a pretty satisfying definition for “game”, again mostly following Fullerton. We know a game is a closed system, meaning it is a complete, self-contained simulation that has no dependencies to events, conventions, or practices existing outside itself. Additional concept or keywords that we want to include in our definition include how the game system thrives on conflict and uncertainty, and is set up to produce unequal outcomes. After all, nobody wants to play a game where one knows who will win or lose right from the start.

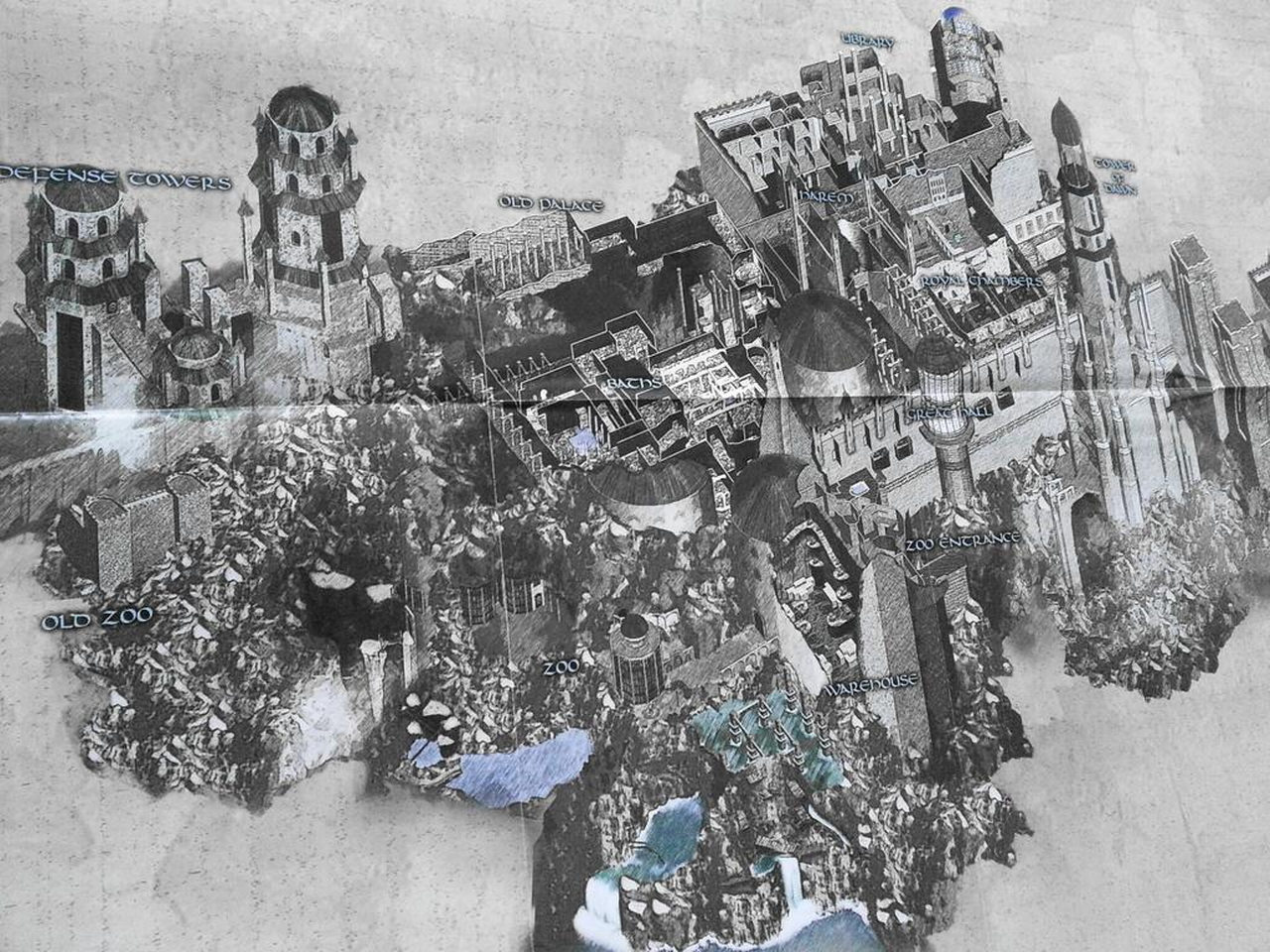

Fig. 2. A rendition of the Palace in the 2003 “Prince of Persia” reboot

But then, aren’t we leaving something out? We sure are. Figure 2 shows a rendition of the palace in which the whole of the formal and dramatic elements in the “Prince of Persia” reboot play out.

This is where you spend the 11 to 30 hours it will take to resolve the story of the prince into an unequal outcome. Isn’t this a set of very important elements? What are rooms and walls and precipices and waterfalls? Where is playing actually happening?Think about Zork: are grues everywhere? Not at all. That would defy their purpose as a game element in the first place. You only find grues in the pitch black areas you haven’t explored yet.

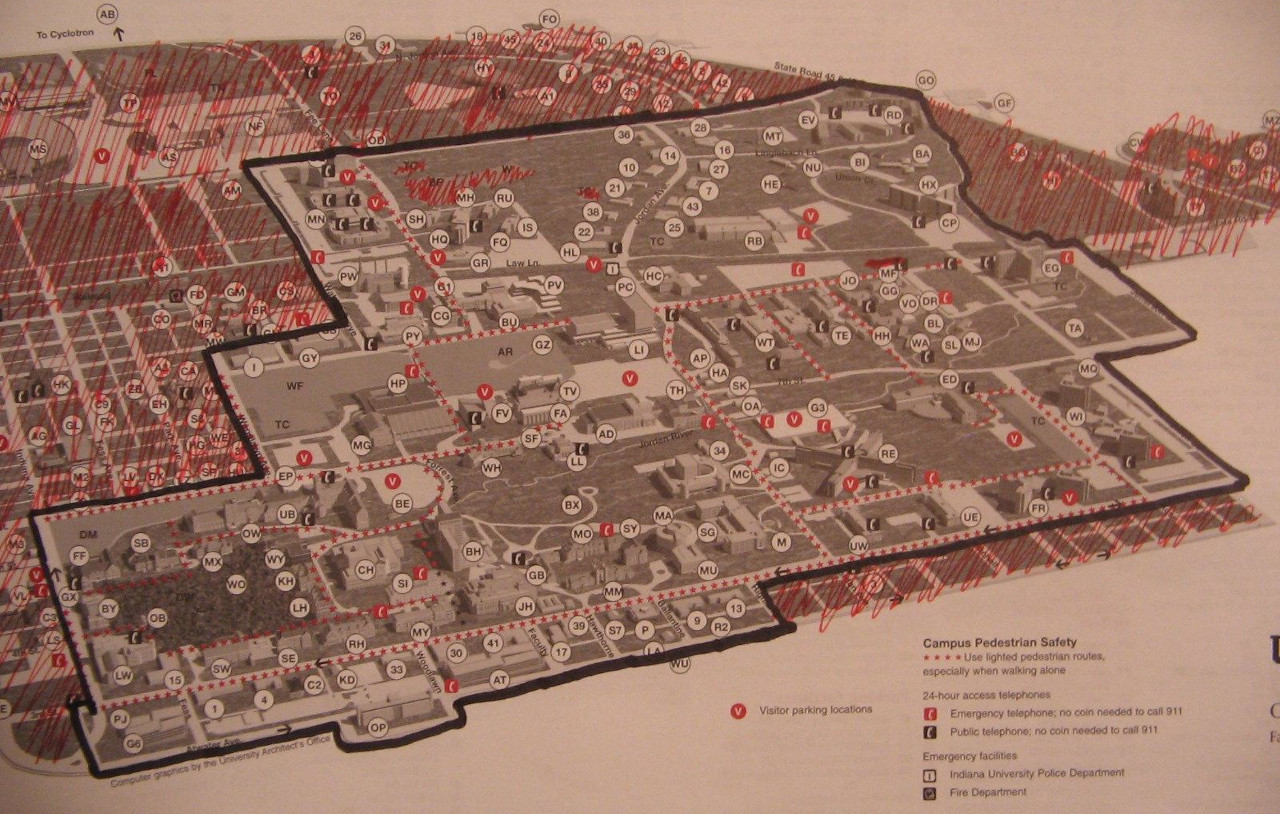

Fig. 3. Humans vs Zombies, Indiana University. Image: P. Guilty. http://www.flickr.com/photos/popeguilty/2696780797/

Figure 3 shows a map outlining the boundaries for a zombie game which was played on campus at Indiana University. Within the borders drawn in black on the map, one could be a zombie and have fun. Outside that black line, in the red areas, you could get shot by a particularly nervous citizen who has seen too many a b-movie. And as a consequence, have a lot less fun.

Or think of a game of hide and seek: does such a game have boundaries? Does such a game possess spatial elements? It sure does. but if you exclude the home base, they are all procedural. You cannot point to a precise boundary, area, or space, but players know they are “in” game space, implicitly or explicitly agree on the extension of game space, and would generally consider running to the airport and flying to Antarctica a form of cheating.

On the other hand, board games such as “Mystery at the Abbey” create a microcosm that is meant to take players somewhere else, where different space/time rules might apply. Players become scientists fighting an infectious disease (Pandemic), colonial governors during the Age of Sail (Puerto Rico), or b-movie characters spending the night in a haunted house (Betrayal at the House on the Hill). Video games can make this “being elsewhere” an immersive experience in which fighting dragons is a commonplace, if not desirable, evenience (Skyrim).

All of these games structure game space as an essential component of play, regardless of whether they do so by procedurally reconfiguring physical space, by recreating a material but allegorical snapshot of a specific time and place, or by immersing the player in a digital alternate reality.

The spatial elements set is the missing piece in that tentative beginning definition. A game is a closed system and an invitation to play and enter its “magic circle”, to quote Huizinga. And a magic circle it is indeed, one in which we willingly suspend reality and its rules and walk for a little while in someone else’s shoes, following different logics for different goals. Can I have a raise of hands for how many here played Doom or Quake and moved on to land a day-to-day job in which they kill alien demons from hell?

But for a magic circle to exist, we need a specific space in which a game has to happen. This space needs to be structured, and my claim is that this space, and consequently its structure, define or significantly contribute to define the very nature of the game itself.

Fig. 4. A game of hopscotch. Image: Nandadevieast, http://www.flickr.com/photos/agnihot/4937763060/

Now, could you have games without having game space? The answer is no. All games happen in some space and this space is an essential element of that specific game. No game space, no game. Even abstract games, such as charades for example, necessitate game space and structure it in a way that responds to in-game constraints. For example, it is possible to play charades over Google Hangouts, but not across the full extent of a football field unless we involve some form of augmentation, aural and visual. That is because charades requires players to be able to hear and see what other players are doing, to directly experience play in the terms set by the game.

In this sense, game space possesses a dual nature: it is both mathematical, made up of cells and lines or algorithms, and experiential, related to our engagement. It also exhibits a few basic characteristics. It can be strictly bounded, like in tennis or SuperMario, or or loosely bounded, like in hide and seek or Skyrim. It can be discrete or continuous: discrete like in chess, continuous like in hide and seek or Skyrim.

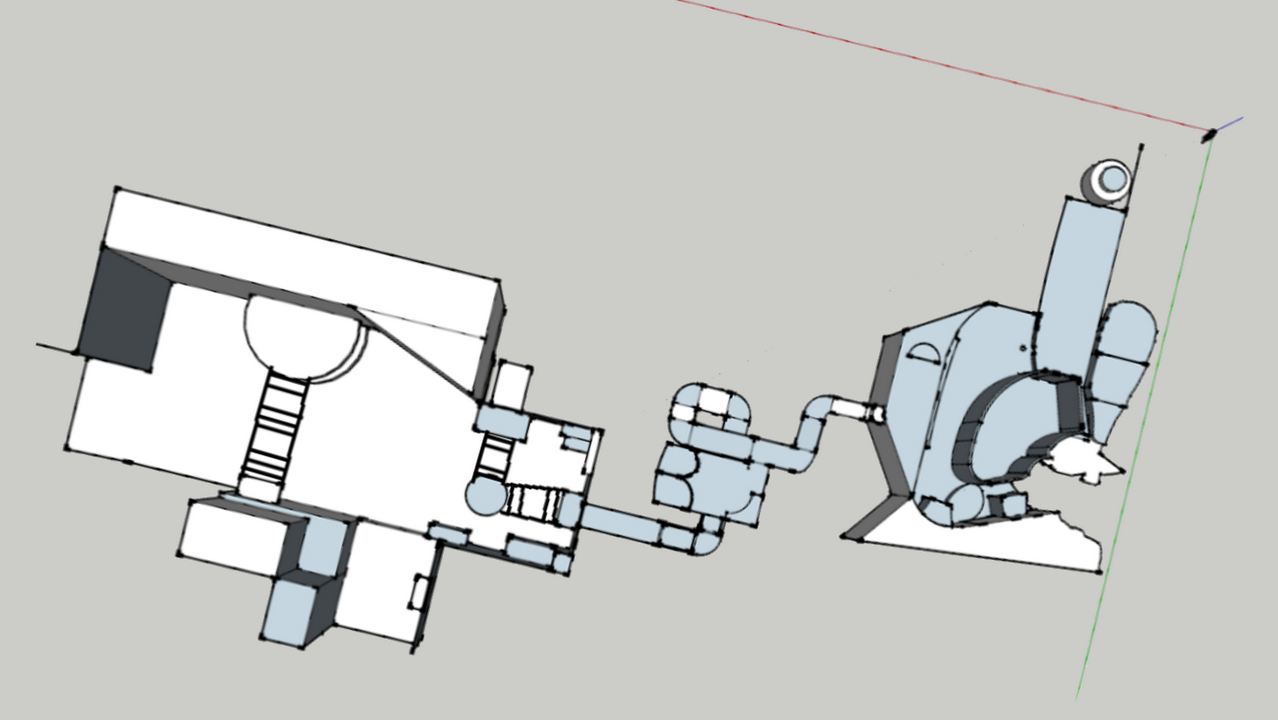

Discretely partitioned game space usually results in a series of connected subspaces. Many games, even when they allow a certain degree of freedom in roaming, actually use a hub-and-spoke or mesh model. Figure 5 shows a hub-and-spoke example: the map of the “Prince of Persia” second reboot (it was actually a reboot of the reboot. I have no idea what one should call such a thing).

Finally, space in games can be mono, bi- or three-dimensional. Monodimensional game space is particularly interesting. We have a prototypical example in the traditional game of the goose board game: this does not mean that the game concretely exists in one dimension, it would be a dot in that case, but rather that “game space”, that is the space configured by and for the game, is a line. The fact that this line is usually coiled up in most versions of the game does not change the fact that players move from a start point to an end point, and then the game is over. Guitar Hero is a very good example of a monodimensional video game. Again, game play happens along a line and there is no going back. Some scholars include circular board games such as Monopoly in this category.

Fig. 5. Hub-and-spoke map in the “Prince of Persia” second reboot

Bidimensional is tricky. Clearly board games that do not use a game of the goose layout are bidimensional. Traditional platformers such as SuperMario are also bidimensional. But what about games such as pool? Pool would appear to be bidimensional, but nothing in the elements of the game prevents a player from making a ball jump, so game space is actually three dimensional. So are first-person- or third-person-view video games.

Let’s examine tic-tac-toe and see how these pairs apply.

Game space is discrete: it identifies 9 cells, clearly delimited. It is a connected space: players play the game by trying to line up triplets of x’s or o’s across the different cells, according to established patterns. It is also a bounded space: symbols need to go in a cell (and nowhere else) and a cell behaves like a binary switch: a symbol is either inside that cell, regardless of actual positioning, or outside of that cell and inside another. Finally, it is a bidimensional space.

In one of my courses, I had students apply the formal and dramatic sets to analyze or deconstruct a few games, and then I had them apply them in combination with the lens provided by the spatial set to the 2003 “Prince of Persia” reboot to verify if and how game space impacted the game experience.

A few groups mapped game space in accordance with a model proposed by Georgia McGregor (2007). McGregor categorizes game space according to the way it engages the player and identifies six distinct types of spaces: challenge space, “where the environment directly challenges the player”; contested space, “where the environment is a setting for contests between entities”; nodal space”, where social patterns of spatial usage are imposed on the game environment to add structure and readability to the game; codified space, “where elements of game space represent other non-spatial game components”; creation space, “where the player constructs all or part of game space as part of gameplay”; and backdrops, “where there is no direct interaction between the game space and the player”.

Fig. 6. The Zoo, Prince of Persia (Image: Lodin, Olovsson, Nilsson, Magnusson, Anic)

Challenge space is a staple of platformers, and students identified challenge spaces as one of the major spatial elements in “Prince of Persia” as well. All of the areas, and there are quite a lot of them, where the prince engages in acrobatics and the game environment “directly challenges the player”, configure challenge space. Contested space is a staple of most strategy games, and is also the other major spatial element in “Prince of Persia”. After any one challenge space, the game brings the prince to areas where he is pitched against ever increasing numbers of increasingly dangerous foes. For the player, this is one more chance to show off that vault-then-stab-then-finish trick that took ages to master. These spaces are distinct and different from those that represent challenge space, and the two never overlap but always follow one another.

Nodal spaces are present as well. For example the secret magic fountains areas the prince visits to increase his overall “health”. Nodal spaces are widely used in video games to represent a specific actionable potentiality that is encoded in an object or place for clarity of play. A good example is the leap of faith ledges in the Assassin’s Creed games. While players can jump off any tower or roof, these are the only places from which you can leap and survive, and they are well marked so players do not get confused and constantly leap to their in-game deaths. Students found this way of deconstructing game space in relation to game play extremely fruitful. One of the immediate consequences was that they were able to identify a spatial rhythm to the game, which was reflected in the way dramatic and formal elements flowed together, and to understand how game space was literally driving the narrative.

To provide a contrasting approach, a few other groups of students examined the game applying Kevin Lynch’s set of spatial building blocks used to create a cognitive map of the environment: districts, edges, paths, nodes, and landmarks. After all, game space is still a human space, designed for a purpose, and relying on the same spatial relationships rooted in embodiment of the physical built environment.

Do we have districts in “Prince of Persia” then? We sure do. The game is built around districts. The Hall, the Zoo, the Baths, the Caverns, the Prison, the Tower. Each of these areas perfectly encapsulates Lynch’s idea of a district as a large area exhibiting thematic continuity, in purpose and morphology, that “the observer can mentally go inside of, and which have some common character”.

Edges, structures that keep you on a path, such as the banks of a river, or the continuous curtain of buildings along a street or a square, are also present in the game, usually providing affordances for movement in challenge space and containment in contested space.

Paths, such as a road or a gravel track in a forest, are an extremely common feature of games. “Prince of Persia” adopts a subtler approach, since figuring out the path is part of the challenges that the game throws at players. Paths are of course present in “Prince of Persia” as well, and their identification and analysis produced one of the most interesting insights in relation to the spatial structure of the game: regardless of how complex the architecture of a specific district looked, the player usually had one way to traverse it, and no ways to go back.

Lynch’s nodes, points of interest and places where things happen or might happen, for example the intersection of streets, exist in “Prince of Persia” both at game level, where the different districts and their narrative sub-arcs act as such, and at the individual district level. Districts comprise a succession of areas, alternatively providing challenge or contested space, and acting as clearly identifiable nodes in game space.

Landmarks are the final element in Lynch’s list of spatial elements. While it could be argued that individual districts provide area-level landmarks whose purpose is to guide the player, the real Lynchian landmark in the game is the Tower of Dawn. Players see it from afar multiple times throughout the game as the narrative constantly hints at the tower as the ultimate destination.

What could be concluded from these analyses was that while the game presents a realistic if fantastic environment, there is no free wandering around. As one of the students put it, “Prince of Persia” is much more similar to a theme park ride than to “The Sims”: forward spatial movement is the only metric for advancement in the game and nothing ever happens if the player does not progress through game space. In this sense, “Prince of Persia” is a glorified (and spectacular at times) game of the goose. It is monodimensional and defined by a rigid structure of dramatic elements that unfolds through a rhythmic succession of alternate spaces: challenge spaces, mostly built around the edge and path spatial primitives, are always followed by contested spaces, where nodes and districts become prevalent. Formal elements also alternate, so that certain actions such as attacking enemies are always performed in contested space and never in challenge space.

The structural arc of the game, its narrative arc, advances in sync with the player’s exploration of game space. The game simply cycles through a 1-hour mini arc of challenge-contend-narrate spaces over and over, and once all of the game space has been explored, the game ends.

This rhythmic structure is so evident once the game is deconstructed from a spatial perspective, that some of the students claimed they did not enjoy playing it that much after they figured it out, since they knew what to expect next. That was an interesting comment: what was then preventing them from seeing this structure when they just played the game?

The short answer is that this progression through space to tell a story is nothing new. We call this type of narratives “quests”, and we have been using them for quite a long time to tie together loose story figments into coherent storytelling. It is the way the “Odyssey” or the search for the Graal are told: we know that the story ends when we have reached the castle, defeated the dragon, and saved the day. Zork is nothing different from this point of view, if not that its world is inscribed into a bi-dimensional game space. And while Zork allows much more freedom than “Prince of Persia” does, exploring its world means exploring and uncovering its story.

Quests weave a narrative through a spatial structure. Without space, there is no story. Without the story, game space is meaningless, empty, fruitless. Uncovering the structure of this relationship through the addition of a spatial set to Fullerton’s formal and dramatic elements helps clarify how the machinery of a game works, and lays bare its tricks. It does not necessarily stop there, though. There is an additional important point that can be made and that can be generalized to all forms of new media, websites, mobile apps, software-generated and digital / physical environments, which are, as Lev Manovich describes in his “The Language of New Media”, all navigable spaces. New media is spatial in nature, and spatiality and spatial ways of understanding can not only illuminate how game space is built and the way it works: they can provide interesting insights into how to structure experiences in all information-based spaces as well.

In Ruben Fleischer’s “Zombieland”, we can see information, meta information that does not physically belong to the scene, entering movie space so “naturally” that we witness characters crashing through the credits. The streaming series “House of Cards” and the movie “Panic Room” are generally credited for early use of such techniques. More recently, and thanks to director of photography Steve Lawes and director Paul McGuigan, the BBC series “Sherlock” has portrayed at least three different representations of meta-information becoming a bona fide artifact in scenic space: text conversations on mobile phones, the content of a webpage, and Sherlock Holmes’s thought processes.

While “Sherlock” gives us a fairly stylish and absolutely abstracted display of the text messages as a 4th wall-breaking “overlay”, whenever they are part of the scene McGuigan feels compelled to also show a mobile phone being used, on a table, or in the hands of the characters. In a scene in which Holmes and Watson are reading Watson’s blog, viewers are given a full scenic-space treatment of the article, which is shown not only as being part of the three-dimensional space of the room the characters are in, but as an accurate typographical rendition of the actual webpage, down to the fonts and layout.

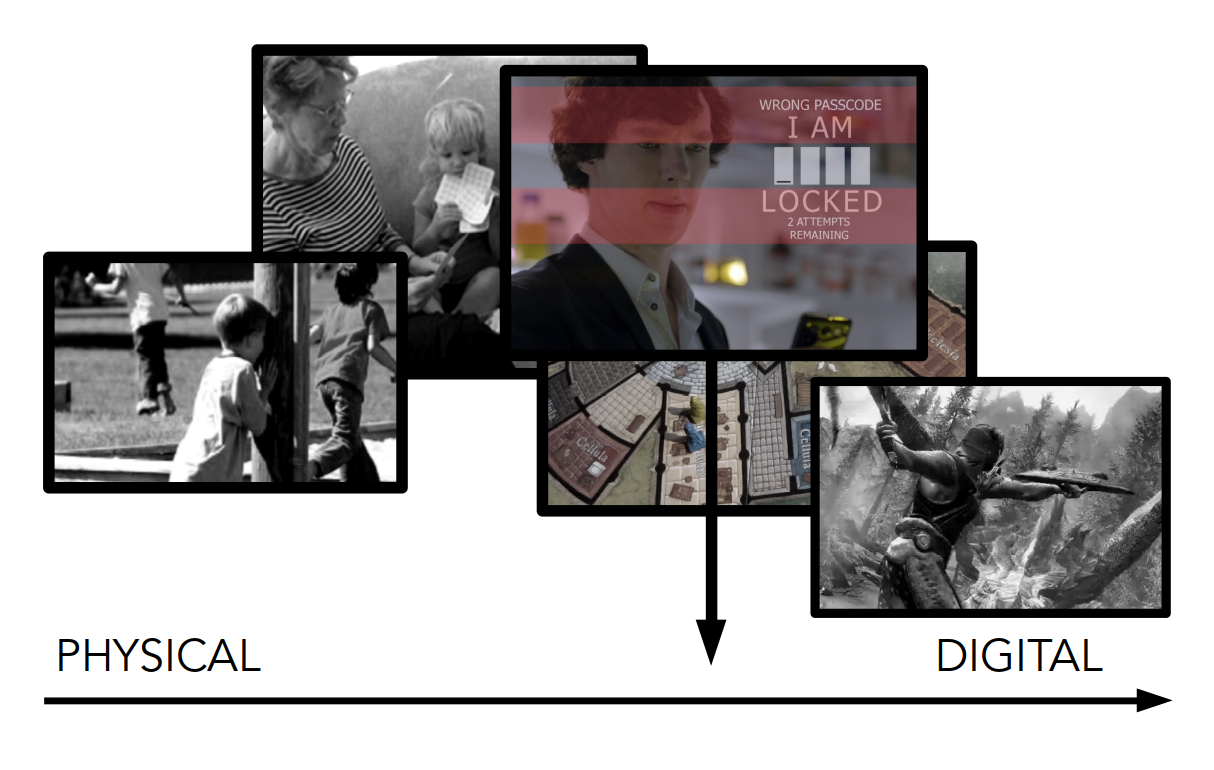

Fig. 7. Physical - digital continuum

If we consider that continuum from physical to digital I mentioned earlier on when discussing boundaries in games, from hide and seek to Skyrim (fig. 7), these scenes from “Sherlock” which comprise embedded pieces of meta information would be roughly positioned slightly after the middle point. Digital is a physical presence, but we need an anchoring: a phone, a computer. For now.

The third and more interesting example of meta information as part of the mise-en-scene in “Sherlock” is when the show makes Holmes’s deductive reasoning process visible. His thoughts are represented as being much more “inside” movie space. They belong more: words float around and attach themselves to people and objects. In an episode in which Holmes becomes perceivably drunk, viewers factually observe his deductions turn blurry and imprecise, and his chain of thought collapse and derail. This is a very different approach, a couple more steps towards “virtuality” or “digitality” as we normally would intend it, but it is also the one case that does not involve computers. Just mental processes. And since the audience has a more intuitive understanding of mental processes, at least more intuitive if we compare it to the audience’s image of how a blog is supposed to work, the director does away with any material anchoring. There is of course no phone or laptop in the scene, but also no pen and paper or post-it notes flying around.

In yet another episode, Holmes is interviewing a number of women via chat, using multiple computers (and not multiple accounts, it’s too early for that). Only most of this scene is played out in his own mental rendition of this multi-sided conversation, a courtroom (he’s investigating, after all). It is an interesting move backwards in terms of the physical / digital continuum: this is a mental space that becomes “real”. Pretty much like a digital space becomes “real” in a video game.

“Sherlock” shows how close we are, and yet still far in some respects, to a mainstream understanding of “virtuality” as it is usually intended, a digital elsewhere. But this is a very successful crime series for generalist broadcasting, this is no Gibson or Stephenson. Something is changing.

In his “The Language of New Media”, Lev Manovich stipulates that we can “be there” in a heideggerian sense either through immersion, in skeuomorphic actionable 3D spaces, or through navigation, in more abstract, database-like environments. Websites and mobile apps for example. I suggest that these two structures or modalities are blending and morphing: people increasingly have lived experience of actionable abstract spaces, and video games are more than partially responsible for it. Where this is leading is beyond the scope of this keynote, so you will allow me to conclude on a minor note, pointing to the fact that an understanding of game space, a way to deconstruct it in relation to the formal and dramatic elements at play, is necessary. We might not think of shopping on Amazon and playing “Prince of Persia” as two similar activities, but we would be wrong. They both set up rules, resources we have or want, outcomes, roles we play and stories we inhabit, and spatial constructs in which these play out. Thinking about all new media spaces as game spaces gives us the luxury of a consolidated body of knowledge to work from. What I presented today is an initial step in this direction, a bridge over the waters of experience design.

So when you play your next game, pay a little attention to how game space plays you. Then do the same when you access your online banking services, I promise it will be, well, illuminating. And always carry a torch. You’ll need it for the grues.

Thank you.

Bibliography

- McGregor G. L. (2007) Situations of Play: Patterns of Spatial Use in Videogames. Proceedings of DIGRA 2007.

- Lynch, K. (1960) The Image of the City. The MIT Press.

- Nitsche, M. (2008) Video Game Spaces. The MIT Press.