March 8 2025 (a 25 minutes read)

Everything Flows

Video and full transcript of the World Information Architecture Day 2025 Global Keynote delivered in 23 locations around the world on March 8 2025.

The text is also available in PDF format over at ResearchGate and the video is also available on YouTube. Full references and license details for the images, videos, music, and sources used in the creation of the video are listed in the Credits section at the end of the transcript. There's quite a few, so if you find any I inadvertently forgot, ping me.

Λέγει που Ἡράκλειτος ὅτι πάντα χωρεῖ καὶ οὐδὲν μένει, καὶ ποταμοῦ ῥοῇ ἀπεικάζων τὰ ὄντα λέγει ὡς δὶς ἐς τὸν αὐτὸν ποταμὸν οὐκ ἂν ἐμβαίης

“Heraclitus says something like this: that all things flow and nothing remains; and comparing the things that are to the flowing of a river, he says that you could not step twice into the same river”.

Plato, Cratylus, 402a. Written around the year 390 BC and revised later

Hoc est quod ait Heraclitus: ‘in idem flumen bis descendimus et non descendimus’. Manet enim idem fluminis nomen, aqua transmissa est

“This is what Heraclitus says: ‘We go down and do not go down into the same river twice’. For the same name of the river remains, but the water has passed through”.

Seneca the Younger, 58th Moral Epistles. Ca. 65 AD

πάντα ῥεῖ

“Everything flows”.

Simplicius, commentary on Aristotle’s Physica, 1313.11. 6th century AD

Transcript

Change.

Change is the only certainty we have in life. We change. The world around us changes.

Change may be something we desire or fight for, or something we struggle with and that we try to avoid.

Individuals. Families. Groups. Organizations. Nations. Mankind.

Change is a challenge, a two-sided coin that seems to mostly land on its edge. For any lucky heads, something new and good, something right and fair, there is some tails along the line, something wrong, something amiss, something broken.

Everything flows, and so does, or should, information architecture. At least, that’s what seems reasonable. Where from and where to, though, is another two-sided coin.

Villa Savoye

I’ve been showing a photo of this house to my students and to junior practitioners since I realized that when I said “think of an old movie” they didn’t picture images from Ridley Scott’s 1982 “Blade Runner” or even the Wachowskis’ 1999 “The Matrix”, but rather from Whedon’s 2012 “The Avengers”.

Fig. 1. Le Corbusier, Villa Savoye, Poissy (Wikimedia).

The photo always comes with a question: what year do you think it was built?

Answers vary little. Usually it’s “in the Nineties”. Some brave soul offers “in the Sixties” now and then. They are all wrong by a long stretch.

In the 1920s

French-Swiss architect Le Corbusier, a giant of early 20th century Modernism, built Ville Savoye in Poissy, near Paris, between 1928 and 1931. That’s when Laurel & Hardy and Charlie Chaplin were big at the box office and life looked like this.

Fig. 2. City life in the 1920s (Image: Unknown).

The answers I receive don’t usually get any better if I get closer in time and leave architecture for human-computer technology.

The mouse

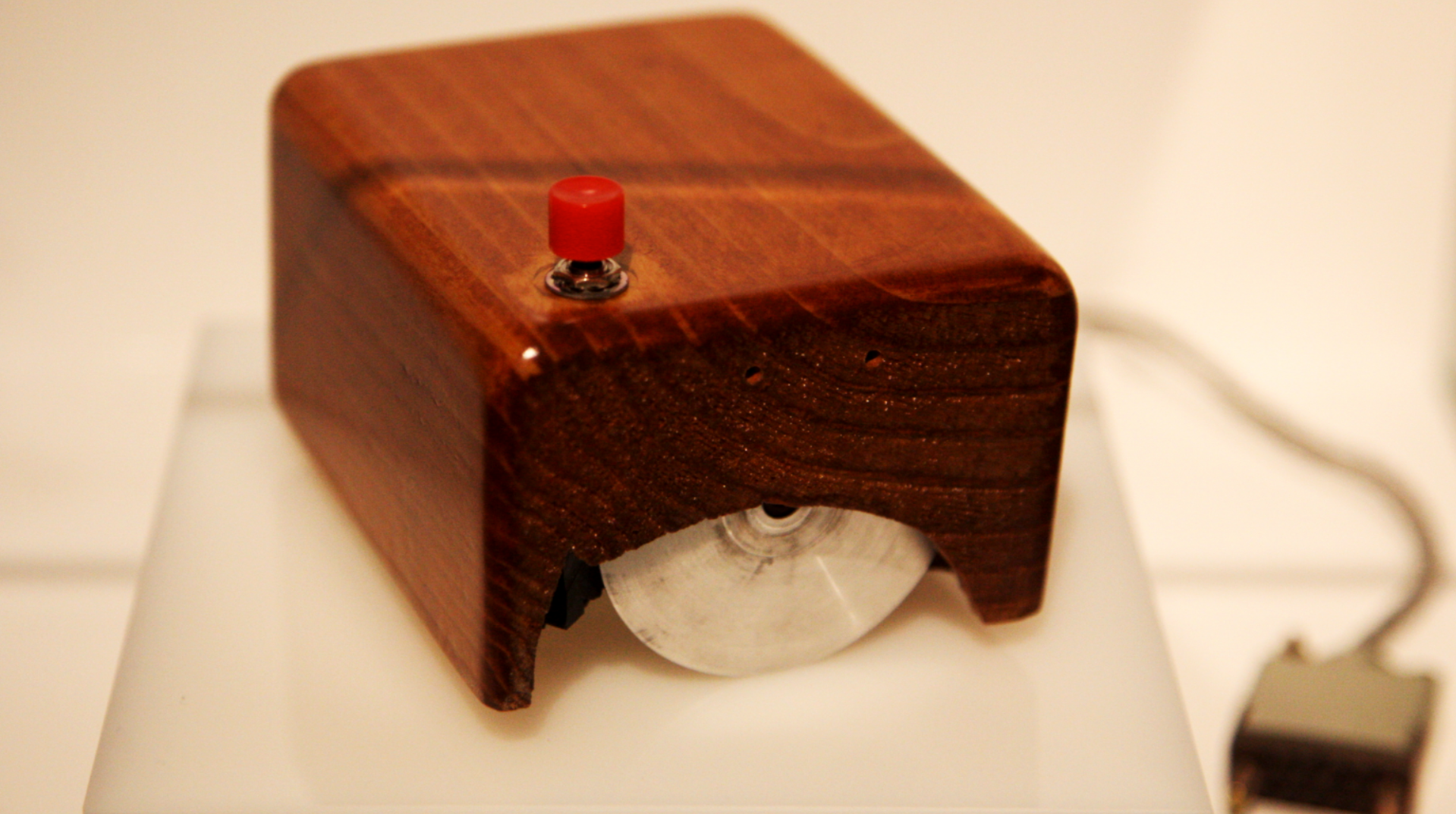

Engelbart’s mouse is now sixty years old, but regularly dated to “the late Eighties” or even “the late Nineties” when shown in class or in workshops.

Fig. 3. Engelbart's mouse, circa 1965 (Image: Computer History Museum).

What we are seeing at play here is characteristically human and magnified by having more years in front of you than behind you—every young person in every generation has believed, at least for a while, that today is the only time that matters. If they weren’t born then, whatever it is we’re discussing must be very, very old. But it’s also something significantly amplified by how digital has changed the world in the past thirty-forty years, and how these changes have changed us, individually and as societies. Our attention has increasingly become the currency we exchange for services, with all this entails. Digital is a constant drive pushing us forward, making these 2020s the years in which we hurry. A hurried society doesn’t stop to think much about consequences. Nor does it have the time to slow down. FOMO. YOLO. All the way down.

Hear this train a comin

These changes brought in by the “information revolution”, the urgency to be here, now, in real-time, rushing ahead, getting there faster even if it means breaking things, have ironically been long coming. Our “digital transformation” is the long tail of a process that started with the electrical telegraph in the 1830s. The wired telegraph was the first large scale technology that could transmit pure information instantaneously over long distances. No need for people, horses, carriages, ships to take a letter, a document, a token across land or sea. The telegraph made space and materiality irrelevant, and in its heyday became the first niche online social media, spawning plenty of operator communities that spent their free time chatting with each other via Morse code. After the telegraph, the rhythm just picked up. With every cycle we made the world smaller and communication faster, more distributed, more accessible: the telephone arrives in the 1870s. The radio follows in the 1890s and grows to a real-time mass media phenomenon by the 1920s. We have television in the late 1940s. Arpanet in the Sixties. Usenet, Fidonet, and the internet in the Eighties. The Web in the Nineties. Mobile phones are everywhere in the Noughties. Smartphones and social media in the 2010s.

Living in the now

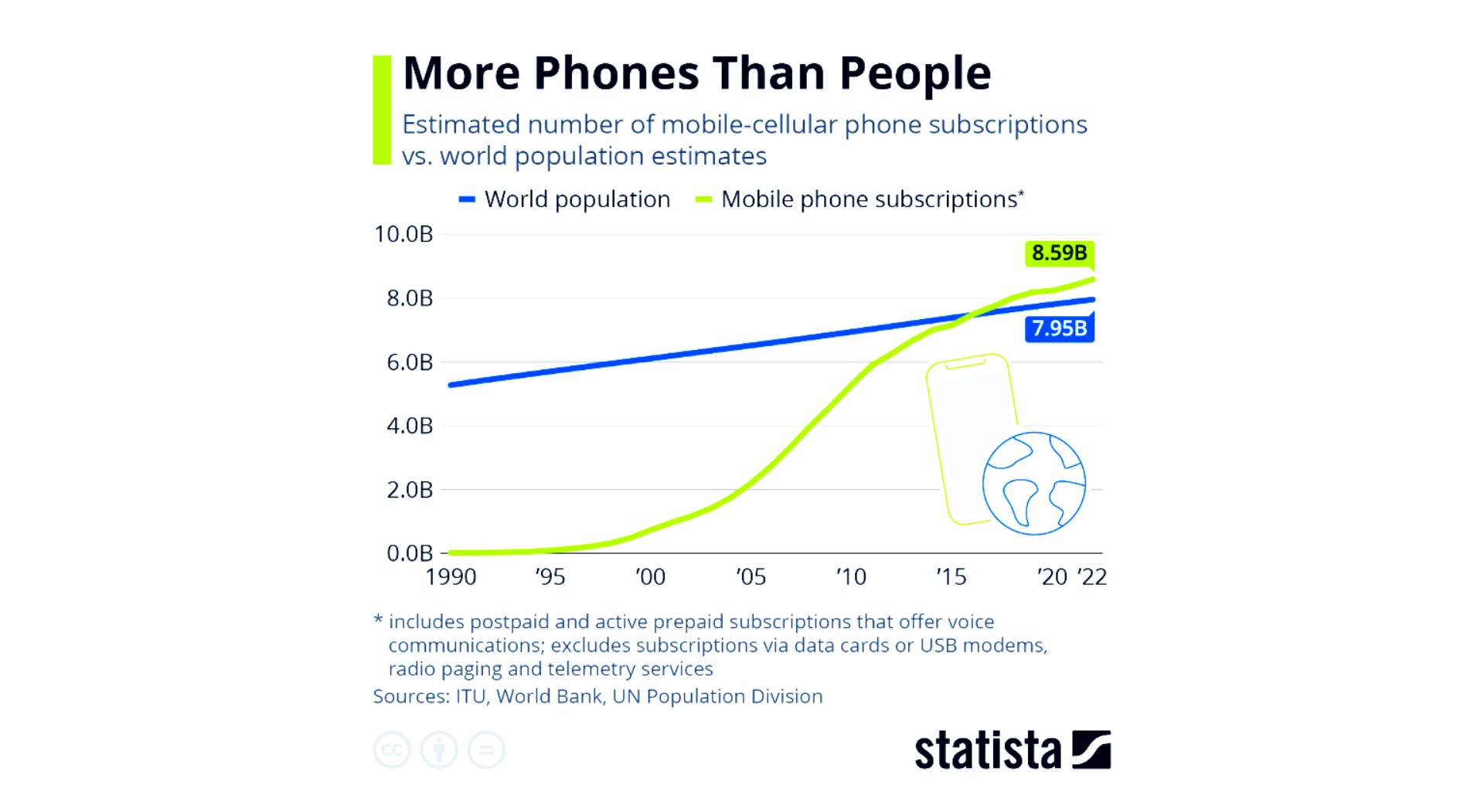

The amount of people with a mobile phone subscription in 1982 tallied up to millions. Today, there are more subscriptions than people on the planet. The amount of digital, easily shareable information we produce, remediate and consume on a daily basis is astounding.

Fig. 4. Mobile phone subscriptions v world population 1990-2022 (Image: Statista).

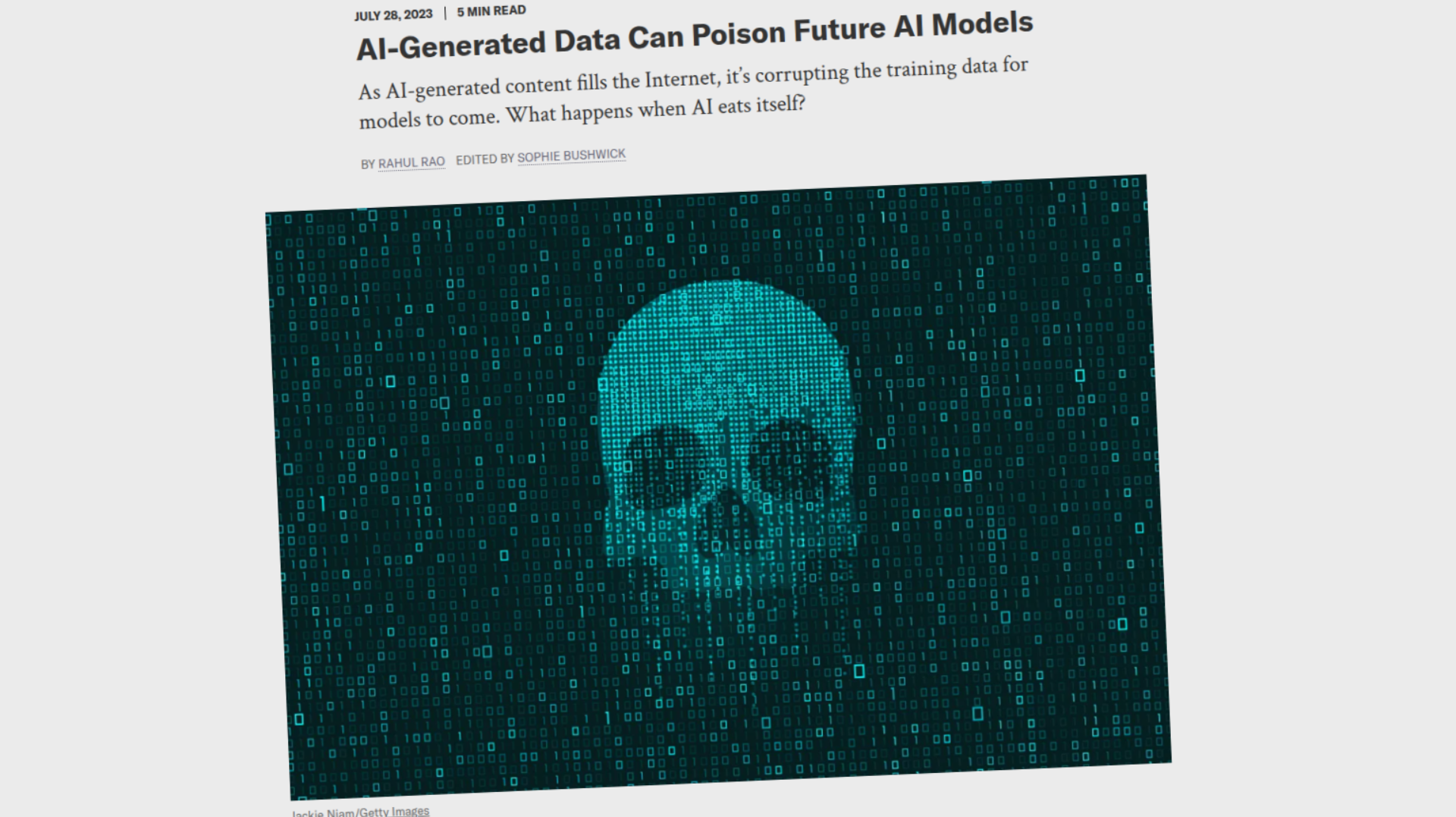

This immersion in information comes with perks, and with plenty of downsides. For every surgeon who gets to save a life thanks to a WhatsApp chat, we have bad actors working to destroy some. For every chance we have to be more and better informed we have a million distracting, incompetent, or plain malicious sources we can’t possibly fact-check, with generative artificial intelligence now poisoning the wells so fast that some researchers believe this horse has already bolted and it’s too late to close the door of the stable.

Fig. 5. AI Generated Data Can Poison Future AI Models (Scientific American).

It also compels us to live our lives constantly dividing our attention between “now” and “what’s next”, pushing us away from “what was there before”. If we’re lucky, we trade some depth for a broader reach. If we’re not, well, we tread into shallow water. In both cases, it keeps us on the wheel, hurrying along, feeding out FOMO, because YOLO.

A history of information architecture

And here’s the problem. Change is hard enough. Not knowing how we want to change things makes it harder, but not knowing the thing we want to change makes it hardest. And telling people what information architecture is, what it was, well, we haven’t been great at that.

If you’re a student or a junior practitioner who wants some information architecture in their life in the 2020s, I’m sorry to say we didn’t make your job any easier. Your sources are most likely to be all over the place. If you are the type who gives up easily, you may end up with a bunch of Medium posts written two years ago or ten ninety second Tik-tok videos. No shade on these. They may be great, but exhaustive they are not.

If you are persistent enough, motivated enough to dig deeper, talk to a colleague or a teacher, get yourself a mentor, engage with the right project or enroll in the right course, and you find your way to projects and writings from the early Noughties or Nineties, it’s hard to avoid that FOMO feeling that you’re reading old, unimportant history, missing out on what’s happening “now”, wasting time you could spend on the next big thing instead. Which is just one more swipe, one more scroll away. Hurry. Look how shiny the future is.

Fig. 6. First WIAD in 2012. Fourteen cities to celebrate 14 years since the Polar Bear book (archive.org).

World IA Day itself is 14 years old. It wasn’t made today. The IA Conference, formerly the Information Architecture Summit, will celebrate its 26th edition in a little more than a month. International events such as the Italian Information Architecture Summit are old enough to order a drink. At least in Europe.

That already makes for some impressive history and quite a few fireside stories, and yet the origins of the field go further back. It may be a surprise to many, but we already have a sixty year long journey behind us: most of us weren’t there, but that doesn’t mean it didn’t happen. So indulge me: let me take you on a short trip down a memory lane you may not have visited before, and tell you about our communal grandparents and great-grandparents. I have this one chance to convince you that adapting information architecture to this evolving world, knowing where it’s going, cannot be done without knowing where it’s coming from.

Forebears: the Sixties

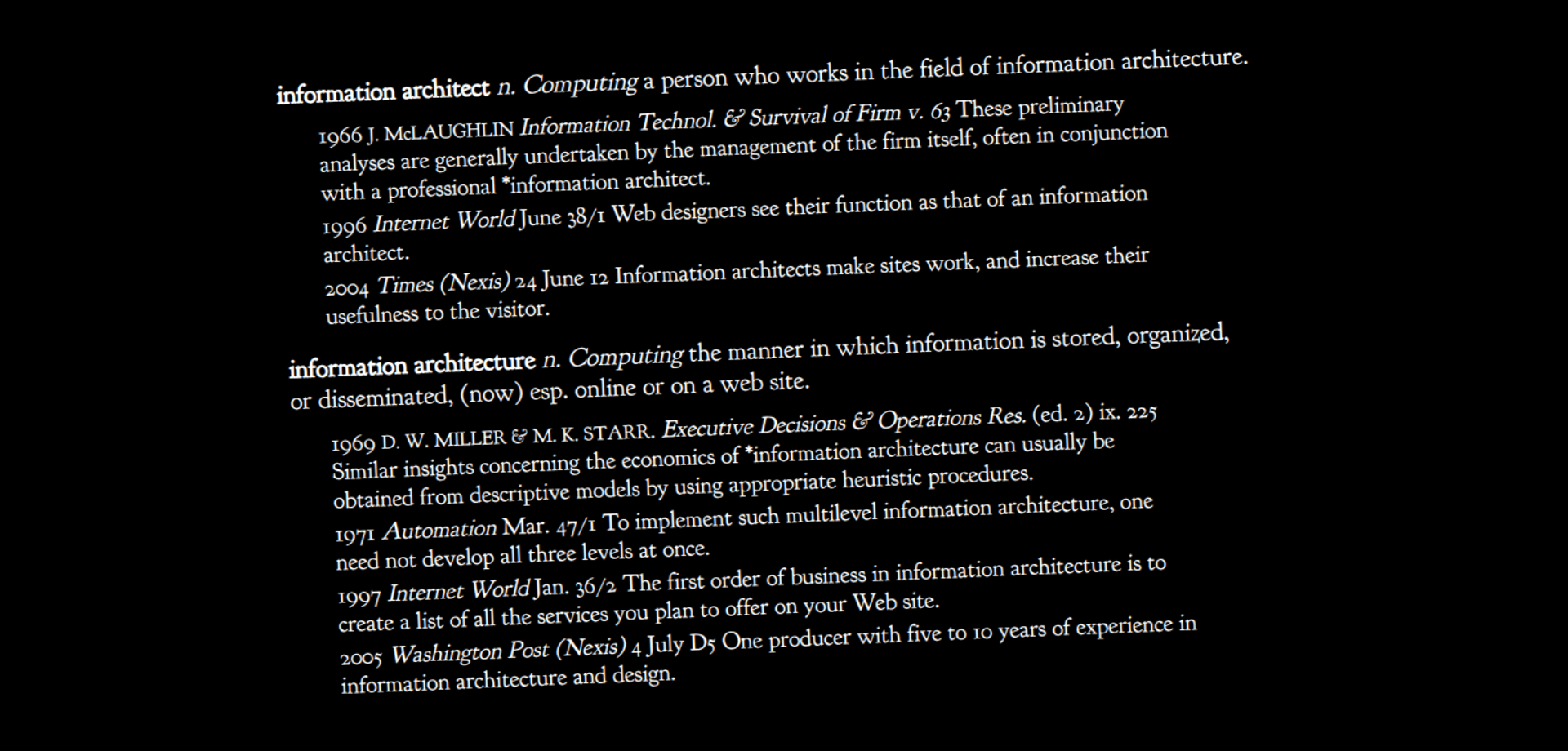

Information architecture as we understand it today sees the light in the Sixties, with the pioneering work carried out in the United States at the IBM Labs and at Xerox PARC on human-computer interactions and system behavior.

Fig. 7. Oxford English Dictionary entry for “information architecture”.

This is also when the terms “information architect” and “information architecture” make their way into the Oxford English Dictionary.

Xerox PARC and Wurman: the Seventies

PARC is famous for giving us foundational computing concepts and artifacts, from ethernet to laser printing, from the desktop metaphor to the GUI. PARC is also the place where, in the early Seventies, work on human-computer interaction and the social aspects of computing is framed as a concerted effort to devise, design, and test the “architecture of information” for the office of the future, and results in the creation of the Alto, the very first personal computer.

The Seventies also see American architect Richard Saul Wurman, the future creator of the TED conference, introduce a modern, profoundly influential formulation of information architecture that we still use today. In a world without the internet and in which PARC sells two thousand Alto computers, Wurman believes that “the explosion of data needs an architecture, needs a series of systems, needs systemic design”.

When asked to organize the 1976 congress of the American Institute of Architects, Wurman naturally centers the event on “The Architecture of Information”. He starts calling himself an information architect, not “a bricks and mortar architect”, but rather the person who puts in place “systemic, structural, and orderly principles to make something work”. This thoughtful making of “either artifact, or idea, or policy” helps “make the complex clear” and creates the “structure or map of information which allows others to find their personal paths to knowledge”.

Anxiety and hats: the Eighties

The Eighties are difficult to read. On one hand, maybe because they expressed different academic traditions and professional worlds, the human-centered vision of technology developed at PARC and Wurman’s architectural push for clarity do not meet. In this void, the conversation shifts: information technology now means mostly injecting hardware into production and management processes, and information architecture begins to be used primarily as a synonym for “computer architecture”.

On the other hand, the last year of the decade sees Wurman publish two seminal information architecture texts. A book, “Information Anxiety”, and a special issue of “Design Quarterly” called “Hats”. Here Wurman introduces what will later become his Location, Alphabet, Time, Category, and Hierarchy approach, LATCH for short, and makes relationships, “the space between things”, central to architecting information. After all, we always “understand something relative to something [we] already understand”. These writings don’t make much of a splash, but plant important seeds that will bear fruit in later years.

The second wave: the Nineties

It’s in the Nineties, with the emergence of the Web and the need to organize and structure increasingly larger amounts of online data, that information architecture finds its niche of opportunity and strikes gold. Lou Rosenfeld and Peter Morville are the central figures of this new second wave.

In 1995, Lou Rosenfeld and Joe Janes open Argus Associates in Ann Arbor, Michigan. Rosenfeld is convinced that “information architecture as a stand-alone service [is] going to boom”, and he’s right. Argus rapidly grows to be a forty-person consulting firm serving big clients who all want to ride the information superhighway.

Peter Morville is the agency’s first hire and, while other notable alumni will follow, Argus’s most important legacy is Rosenfeld and Morville’s 1998 “Information Architecture for the World Wide Web”, still the most widely known and successful book in the field. The “polar bear”, as it’s familiarly known because of its cover, draws heavily from library and information science and establishes taxonomies, classification, and labels for online content as the domain of information architecture.

Argus Associates is the pebble that starts the avalanche. Special groups, local meetups and mailing lists pop up in the US and around the world. A yearly conference, the Information Architecture Summit, is convened for the first time in 2000 in Boston. Two years later, Lou Rosenfeld and Christina Wodtke, one of the godmothers of information architecture, lead a bunch of visionaries to found the Information Architecture Institute.

Crisis: the Noughties

As much as the Eighties, the Noughties are a contradiction. In the United States, the bubble of investments that has supported the early growth of the Web bursts. Andrew Dillon, one of the academics who took an early interest in the field, remembers how “the initial excitement got blown out of the water” all of a sudden between 2001 and 2002. As the economy suddenly contracts, the dot-coms are erased from the board, the importance of an online presence is questioned or deprioritized, and other factors, such as the rise of Google, the new emphasis on interactivity and the Web as a platform brought in by O’Reilly’s Web 2.0, and the emergence of tagging and user-made folksonomies contribute to an unexpected contraction of the practice that hits the field hard. A shrinking market produces conflict and stagnation. Many read these as signs of an inevitable, impending death of information architecture. On the other side of the Atlantic, someone disagrees. The European Information Architecture Summit has its premiere in Brussels in 2005, and is followed by the Italian IA Summit in 2006 and by the German IA Conference in 2007.

In that same year, Jesse James Garrett delivers his “Memphis Plenary” at the Information Architecture Summit. Garrett notes how the field still lacks a language of critique and “ways to describe the qualities of an information architecture [so that one] can tell good from bad”. Most seem to only hear that everyone is in the “experience business”, and by the end of 2009 sister UX conferences open their doors in Brighton, London, and Australia. Many more will follow.

It’ll be in the 2010s that, as Wodtke puts it, “a necessary discipline” reemerges anew. Personal mobile computing and ambient devices move digital information out of the screen and into the world, and a few people take notice.

The third wave: the Tens

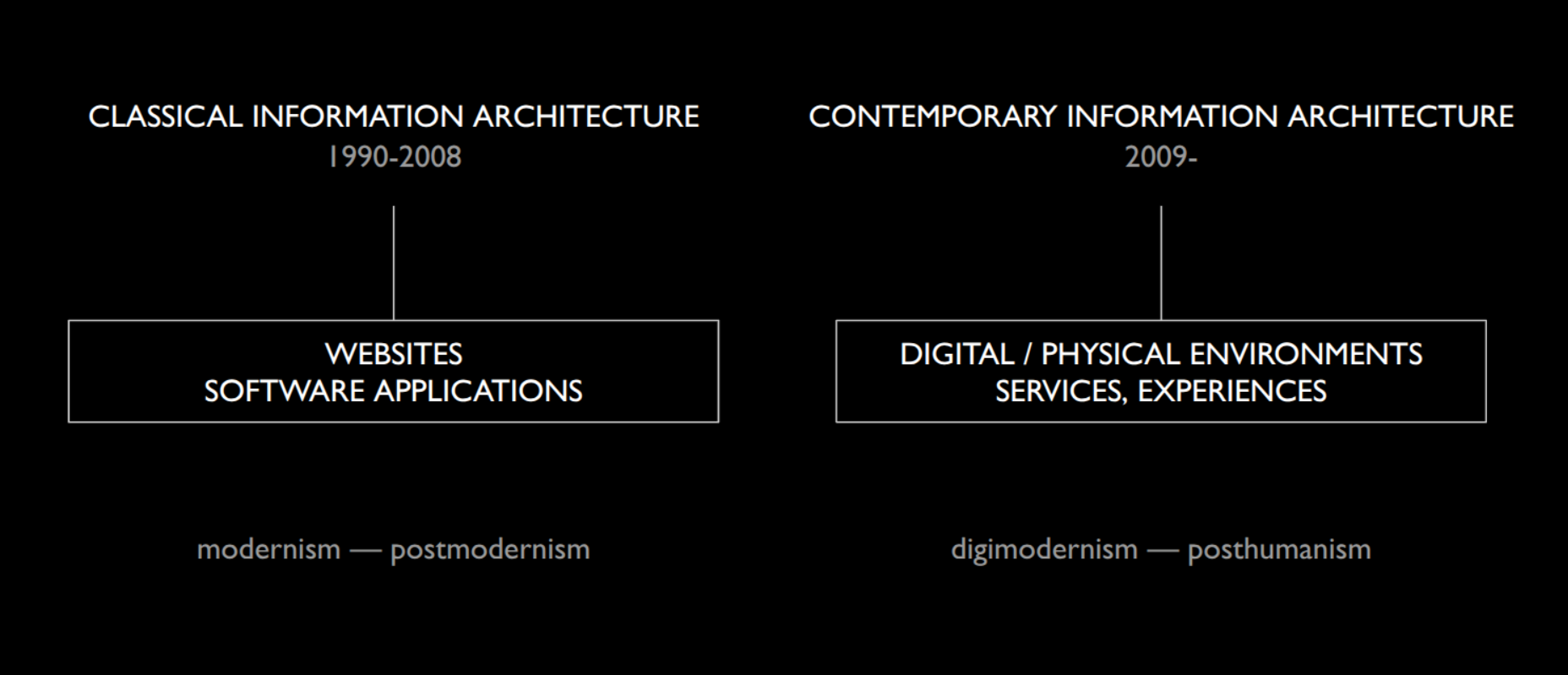

As much as the birth of the Web was the catalyst for a second wave steeped in library and information science, what I call Classical Information Architecture, the bleeding of the Web and digital information into the built environment that begins in earnest in the late Noughties is the catalyst for a third wave, what I call Contemporary Information Architecture.

Fig. 8. The first Reframe IA Roundtable in Baltimore (Image: S. Maxwell).

This third wave is not a rejection of Classical, polar bear information architecture. It’s an enrichment. The information spaces we have been designing for the past thirty years have changed around us. They are not just catalogs, libraries that we access via a screen in a room somewhere. They are the complex, layered spaces that exist between devices, services, locations, and people in which our experiences unfold. Some parts of them are distant in time, some in space. Some are not digital at all. And we are in them. Look around: digital is enmeshed into the physical world in a thousand different ways. It is there, it’s banal, it’s only noticed when it’s absent, as Negroponte wrote in his 1998 “Beyond digital” piece for Wired.

We have long compared an information architecture to the water piping that runs through a house. Good piping is banal and uninteresting. No one cares about it as long as you have taps where you need them, can run a bath or take a shower, and there’s no water on the floors. But everybody cares when you have no taps in the kitchen or the piping leaks every other week. Good piping and good information architectures are invisible, and so is digital now. We only pay attention to it when something goes wrong or doesn’t work.

So Classical Information Architecture would naturally focus on how to design a website, and pay specific attention to the structure and language of the individual pages, at the relationships between the pages, and how to carefully balance content, context, and people’s goals. Wireframes, diagrams, maps, and language documents are typical deliverables.

Fig. 9. Classical and contemporary information architecture.

Contemporary Information Architecture does not represent a discontinuity. The theories, methods and tools of Classical Information Architecture are not going away. Those roots are solid.

It is an extension, the recognition that the work of many practitioners and some scholars commonly stretches outside of the traditional boundaries of the field. Voice interfaces, shared mobility, wearables, house automation, smart environments.

Its focus is on postdigital, rather than digital, experiences: experiences that take place in the discontinuous blended information space in which people move from a mobile app to a store, from a real-time display to a card reader, from a website to a classroom, without ever worrying, as long as everything works, whether any single moment is either digital or physical. Context assumes a new relevance and a new meaning, that of a precise space-time moment in the world, making embodiment, spatiality, policy-making, and place-making a necessary concern of the field.

Thirty years after

It’s now thirty years since Argus Associates. Almost fifty years since the AIA congress on “The Architecture of Information”. More than sixty from PARC. We have the gift of hindsight. Knowing where we come from, knowing where we stand, we can now take a good look at the bigger picture and at the slower patterns that shaped information architecture, both good and bad, and use them to trace a path forward, to try and adapt information architecture to the evolving world of the twenty-first century.

Everything flows

Change can be hard. Humans are creatures of habit. We resist moving on, letting go.

All the same, we won’t adapt if we don’t let go of the identification of “information architecture” with “making websites” that took hold between the late Nineties and the early Noughties.

If you still think in those terms, or have maybe updated your definition to “making mobile apps”, I want you to listen, and not to me. Go back to Wurman, to Rosenfeld and Morville: “making the complex clear” or “designing shared information spaces”, their vision of information architecture, it does not stop at representations of pages on any screen. It never did.

This is not a matter that concerns one’s individual professional practice. Some of us will design information architectures for websites and mobile apps only until they pry the last one out of our dead cold hands. That is fine. That is healthy. But many others don’t. Some design the information architectures that structure state- or city-level systems, policies, products, services, experiences.

This concerns the evolution of the field. We cannot keep defining information architecture through the incidental outcomes that brought it to the mainstream in another century. Websites were the only shared digital information spaces we had. They’re not anymore. Digital-physical information space is where we live now. Not an elsewhere, not “the web” as a separate world, but an ever-present layer tightly integrated into the fabric of reality.

We took more than 5 billion photos per day and around 1.7 trillion photos total in 2024. How would you feel, what would you think of me, if I told you that those almost 2 trillion photos are not really photography, since no film cameras, dark rooms, and chemical baths were involved?

Information architecture is websites as much as photography is dark rooms and baths: not much. They were, incidentally, along the way. Both are constantly evolving practices with their social and professional do’s and don’ts, their theories, their principles, their heuristics. What information architecture doesn’t have compared to photography is a clear, consolidated idea of where it came from, a formalized body of knowledge to tell what’s good information architecture and what isn’t. Garrett told us, but we haven’t really listened, have we now?

The world we live in is very different from the world of the mid Nineties when Argus had to convince prospective clients that this internet thing was for real.

Digital information has become a pervasive, integral part of the fabric of reality in a way that was barely imaginable outside of cyberpunk novels back then. Much of the world walks around with magical tricorders in their pockets. Can you really believe that the transportation system in London doesn’t have an information architecture? Do you really think that when TESCO launched their shopping system for the Seoul subway they did it without designing its information architecture?

All of this real-time, on demand information is architected. And the hole runs deeper than that.

Disneyland has an information architecture, one built to keep you happy, make you move through the park, eat more than you should, and fill up the mouse’s pockets.

Books have an information architecture. If you can find a specific page or a chapter and you know where to find the name of the author, it’s because there is an information architecture in place. Houses have an information architecture. A kitchen is not a bathroom. Songs have an information architecture made of intros, verses, choruses, bridges, bars and keys, and more. Our favorite grocery store has an information architecture, our closets, gardens, appliances, have one.

All things, artifacts, systems, concepts, policies, have an information architecture.

You may dislike calling it that, you may have never thought about it that way. Call it “structure” if you prefer, but that doesn’t change the fact that this is what information architecture is about: the structural backbone that supports an experience by making sure that what is complex is understandable, visible, and actionable.

The information architecture, to use an old example we owe to Jorge Arango, is why we can play chess on a chessboard, on a computer screen, by mail, with people, or just using pen and paper. The interfaces we use and the interactions that result couldn’t be more different. They are specialized. What remains constant, what gives continuity of meaning regardless of what type of chess we’re playing with is the layout of the board, the number and roles of pieces, and the rules and procedures that allow us to play the game. The information architecture of chess.

Once we move past the mental trap we built for ourselves, once we jump out of the fishbowl and into the river, we have to take a deep breath and realize that digital is not an alien realm given to us by interdimensional beings. The structures we create in digital space are the abstraction of the structures we create in physical space. We only know the world by being in the world, being emplaced, being here. We built homes on the Web because we build homes in our cities. Embodiment and spatiality give us primitive, powerful levers—big, small, center, left, top, bottom, close by, far away, hidden, visible, and on—that become metaphors, blends, juxtapositions, structures that we use to create orders, and carefully weave these orders into information architectures.

The future is yours

Scholars such as David Benyon and information architects the likes of Peter Morville, Andrew Hinton, and Marsha Haverty have already pointed out how information architecture cannot be but systemic, ecological. We live in information.

All space is human space, and human space now blends digital and physical, the screen and the world. The world embodies information, information is embedded into the world.

So we need information architecture to make our day-to-day experiences and our connected lives more humane, meaningful, valuable, for everyone.

We need information architecture to make artificial intelligence human- and planet-centered. There’s social and cultural coloring, economic and ideological choices, power-relations and exploitation, and of course politics deeply embedded in the processes we currently use to build and train models. Yet we treat it as a mathematical problem, ignoring the messiness of the world in which we embed it.

We need information architecture for cars, drones, robots, all connected things that acquire, process, act on and transmit information, and we need information architecture for extended reality spaces—augmented reality, mixed reality, and virtual reality environments—where embodiment, presence, and architecture are an intrinsic part of our making sense of the information that surrounds us.

We need information architecture to help us understand and solve the world’s pressing social and environmental challenges.

So, sixty years plus from PARC and fourteen years into the success that is World IA Day, how do we adapt information architecture for an evolving world?

Let go. Reframe.

Information architecture flows in the spaces that connect everything: people, places, products, agents, and services. Its purpose is to make the complex clear. And making the complex clear has never been so valuable. Go on, flow on. The future is yours to make.

Credits

-

Greek voice-over, Plato’s quote: Evaggelia Gkouskou

Latin voice-over, Seneca’s quote: Livia Mariella for Architecta

Class footage: Melania Mihailcea

Thanks to D. Klyn, S. Bailey Fast, K. Instone, B. Bronzino, L. Mariella, D. Gkouskos, E. Gkouskou, M. Mihailcea, C. Pallé -

Richard Saul Wurman photos

Courtesy of the Wurman Archive

R. S. Wurman and Dan Klyn, photographer: Adam Stielstra

R. S. Wurman in the 2000s, photographer: Asa Mahat

Wurman at the AIA 1976, Wurman Archive -

Argus Associates photos and images

Courtesy of Samantha Bailey Fast and Keith Instone

Argus Associates building Google Maps -

Jesse James Garrett’s Memphis Plenary video

Courtesy of Chris Pallé, on Vimeo -

Movie excerpts

Blade Runner (Warner Bros.), The Matrix (Warner Bros.), The Avengers (Marvel / Walt Disney Pictures), and They Live (Universal Pictures)

All rights property of the respective copyright holders.

Excerpts used for educational and informational purpose only, under Fair Use provisions. -

Paul Simon’s interview on The Dick Cavett Show

All rights property of the copyright holders, used under Fair Play provisions

Excerpt used for educational and informational purpose only, under Fair Use provisions. -

Images, videos, screenshots

Annushka Ahuja, Dark Room. Pexels, Free to Use - Aussie~mobs, Tower Street, Leonora, W. A. Early 1900s. Public Domain

- Archeyes, Ville Savoye, interior

- Computer History Museum, Xerox Parc - Office Alto Commercial

- Darcy DiNucci, Fragmented Future

- Europol, International operation takes down another encrypted messaging service used by criminals

- Jim Forest, Tree with roots. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

- GoodFon, Platypus. Free to Use

- Melissa Heikkilä, How AI-generated text is poisoning the internet. MIT Technology Review

- John Madil Fidonet Logo

- Stuart Maxwell Notes from the 2013 IA Summit, Baltimore, MD

- NASS, Paris in the 1920s, excerpts

- National Company Photo Collection, No. 2493. Public Domain

- Picryl, Bell’s first telephone, Chart of the submarine Atlantic Telegraph, Barclay telegraph instruments. Public Domain

- Rahul Rao, AI Generated Data Can Poison Future AI Models. Scientific American

- RawPixel, Team director. Public Domain

- Felix Richter, More Phones Than People. Statista

- Mike Rohde, Wireframes and Search ideas. CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

- Trusted Reviews, OnePlus Watch 2

- Wav Monopoly, Song structure

- Wikimedia, Incunabula, Morse telegraph, Woman using MaaS. Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International

- Wikimedia, Human chess, Leningrad. Public Domain

- Wikimedia, Live chess, Monselice. CC BY-SA 2.5

- Wikimedia, Old Television. Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication

- World Heritage (UNESCO, Fondation Le Corbusier), Ville Savoye, under construction

-

Images and videos from Pixabay

Used under the Pixabay Content License

Adege, Clouds ; AiVreaSaStii, Zoom out ; anijom, Smartphones ; ArtDio2020, Internet ; Artxroom, Coin ; BlenderTimer, Dandelion ; borhan335, Particles ; cipnt, Network ; Congerdesign, Old camera ; Cover-free-footage, Crosswalk ; Cover-free-footage, Kids playing ; Cover-free-footage, Man walking ; ChrisFiedler, Paper ; ChristianBodhi, Skyscrapers ; DariuszSankowski, Navigation ; DavidHoltzer, Library ; dh672480, Timeline ; Elbollobollo, Chess players ; ElenzaPhotography, Fishbowl ; Fernandozhiminaicela, Girl taking photo ; frankspandl, Graffiti ; gagnonm1993, Film ; Garten_gg, Sudoku ; Geralt, Smart home ; gomiche, Computer chess ; juanrendonprod, Harddisk ; KIMDAEJEUNG, Dandelion field ; MagicTV, Traffic ; Maria_Domnina, Card reader ; Mariya_m, Water tap ; MingMedia, Vietnamese fields ; mootlak, Ink ; msufyanali, Like ; Mustakor, Ocean ; Naéeem, Parade ; ninosouza, Livestreaming ; Nova_27, VR World ; olenchic, Propaganda ; olenchic, Clock ; OrcaTec, Chess game ; PIX1861, Devices ; Pixabay, Crowd protesters ; padrinan, Static ; riaz-baloch, ChatGPT ; riaz-baloch, XR ; RPXStudio, Earth ; RyanMcGuire, One way street ; SAHN_VIT, City from above ; SAHN_VIT, Walking ; simonprodl, Data ; Stocksnap, Bananas ; tiburi, Tube ; TommyVideo, Blue Matrix ; Variousphotography, Road traffic ; Vika_Glitter, Camera portrait ; wastedgeneration, Alarm clock -

Music

Used under the Pixabay Content License

Music_For_Videos, Inspiring Emotional Uplifting Piano and Silent Movie Old Record Version; Octosound, Redbone; JuliusH, Heartbraker Blues; Playsound, 80s Retro Synthwave; Kulakovka, Bloom; Clavier Music, Soft Background Piano; Jonathan_DiazPro, Inspirational Piano; Morse Code Generator, Morse code sound (w/ easter egg)